“King of the Coachbuilders”

That’s what Motor Trend called Howard “Dutch” Darrin back in early ’53 – and with good reason. His accomplishments in design and coachbuilding in the prewar years was legendary and his connection with the Hollywood “Prop-Set” (there weren’t jets yet gang…) was remarkable.

He was creative, industrious, innovative, and in demand. And in the same month and year this article appeared, the Kaiser Darrin sports car had its first public debut and became a committed project, and by doing so the Kaiser Darrin became America’s first announced production sports car.

“Dutch” was at the top of his game, and Motor Trend knew it, and I’m sure it was with great confidence that they published an article about Dutch and his prewar and postwar accomplishments.

As I’ve always said, if you want to understand the car, you have to understand the man behind it. So grab a cup of java, get a Cinnabonn (my favorite breakfast food before good friend Guy Dirkin forced a change in my diet) and curl up with your computer monitor. This is a long article, but definitely worth the time it takes to get to know Dutch, his accomplishments, design, and cars.

Off we go….

Le Roi Des Carrossiers: “King of the Coachbuilders”

Motor Trend, February 1953

By Jim Earp

“Dutch” Darrin has carved for himself a remarkable career which, perhaps, has not yet reached its peak.”

DARRIN OF PARIS

That was the sign on a new showroom right in the heart of Hollywood’s exotic Sunset Strip. Now Hollywood could never ignore a sign like that. Rumors whispered through the town by way of the usual well-oiled channels. It became known that he did not make dresses, he had never “coiffed” a hair-do, but that he had designed fabulously luxurious limousines for King Alfonso of Spain and Leopold of Belgium. “The crowned heads of Europe!” the whispers said.

Fascinating stories continued to drift through the studio lots. They told about the Paris autoshow where Darrin was engaged as a design consultant by Minerva, Panhard, Daimier-Benz, Armstrong-Siddeley, Renault, Citroen: all the great auto manufacturers of the continent. After the show, at a dinner given for the most famous designers of the day, Darrin was put on a throne and crowned King of the Coachbuilders–Roi des Carrossiers.

The ever-cynical press agents were considerably shocked, and Hollywood became somewhat breathless when it was discovered that all these rumors were uncontestably true.

Marlene Dietrich and Norma Shearer already drove $24,000 Rolls-Royces that had been designed and constructed by Darrin in Paris; and soon the “Parisien” designer was building special cars for Dick Powell, Clark Gable, Errol Flynn, Donald Meek, and the Countess Dorothy Di Frasso.

Darrin had definitely “arrived.”

Hollywood could not resist the lure of a French designer; and somehow the rumor never did insist on the fact that the fabulous Howard A. Darrin of European renown is as American as Coney Island. Darrin chuckles as he remembers those days. “With a name like Darrin, and that sign ‘Darrin of Paris,’ everyone automatically assumed that I was French. In Hollywood that was worth more than all the work I had ever done.

Of course I had been designing cars in Paris for 15 years, so why should I tell anyone that my ancestors were American pioneers, or that a Darrin fought in the American Revolution? It would just have disappointed them. I don’t remember that I ever actually told anyone that I was French, but then I never did discourage anyone who wanted to think so.”

Darrin has a natural instinct for showmanship; he is a born promoter. And both his ideas on designs and the cars he has constructed are as bold and original in their concept as are his schemes to attain financial backing. That is why he has reigned as king of the coachbuilders for 30 years. Darrin the artist and Darrin the business man worked as a smooth team when he first started in Paris. He and Tom Hibbard had gone to Paris in 1922 as representatives of the budding LaBaron Company, but they soon realized that the wealthy tourists from all over the world, represented a gold mine to enterprising coachbuilders.

Then Darrin noticed that there was no agency in Paris for the Minerva, although the cars sold well in the United States for $13,000 to $15,000. Their well-scrubbed American faces shining with hope and promise, Messrs. Hibbard and Darrin scurried off to the Minerva factory in Antwerp, Belgium.

They proposed simply that they be given the Paris agency for the Minerva. When the Belgians pointed out that Minerva had never sold more than a car or two a year in Paris, Darrin unfolded the plan in detail. They would sell chiefly to Americans planning an extended stay in Europe.

They proposed simply that they be given the Paris agency for the Minerva. When the Belgians pointed out that Minerva had never sold more than a car or two a year in Paris, Darrin unfolded the plan in detail. They would sell chiefly to Americans planning an extended stay in Europe.

They could drive the car while sightseeing, then ship it home, taking advantage of the duty exemption on used property. The car would arrive in the United States at a total cost much lower than the New York price.

The Belgians were impressed with the idea but finally rejected it on the grounds that it would ruin their New York agent. Darrin then promised that the price would be set high enough so that no customer could get his car home for less than $11,000–a reasonable saving for a used vehicle.

After the Belgians extracted an additional promise that all cars would remain in Europe for six months, they demanded $20,000 as a guarantee that the price level would be maintained.

Neither of the partners had anything approaching that sum of money, but they had nerve and inspiration. Rushing back to Paris, they were just in time to rent space in the Paris auto show. By burning gallons of midnight oil, they sketched a number of special bodies for the Minerva chassis and hired an artist to complete full color drawings. They were, of course, unable to display a car, but with great aplomb they hung their pictures under a bold sign reading, “Minerve de Paris, Minerve de France.”

When the crowds poured into the Grand Palais opening day, Darrin began circulating from stand to stand. Whenever he located opulent-looking Americans gazing at the lush limousines displayed by Hispano, or perhaps Rolls-Royce, he would strike up a conversation that leaned heavily toward the beauty and virtues of the Minerva. In case anyone ever doubted his generous statements, well, there were pictures to prove it.

After the show they were able to return to the Minerva factory with orders for 20 special bodies and $40,000 cash, representing a $2,000 deposit on each car. According to the terms of the agreement, the customers were to pay half the price of the car upon delivery of the chassis and the balance on completion of the vehicle.

After this convincing demonstration of the art of lifting oneself up by one’s bootstraps, the resistance of the heads of the Minerva firm collapsed completely. Perhaps they considered the hazards of having these two young men as competitors. They even withdrew their demand for the $20,000 bond. In case this transaction does not seem incredible enough as it stands, there is one more point that can be mentioned. Darrin sold those Minerva town cars for $8,000 or $9.000 each. The entire chassis, complete with the engine and all the running gear, cost him $600 at the factory.

The firm of Hibbard and Darrin was soon solvent. Darrin was free to work out the wealth of revolutionary ideas that flashed into his consciousness in an inexhaustible array.

One of the first automobiles he designed in Europe featured sliding doors. In 1926 he designed two Rolls-Royce convertible sedans (see page 35, top right photos) that set the trend in styling for the next 10 years.

They were the first cars that Darrin knows of with rounded sides. Fifty units of each model were purchased by Rolls-Royce of America–the first large-scale production order the firm had received.

General Motors adopted the impressive hood, sides, and fender lines of these cars for its production Cadillac and LaSalle, and paid Hibbard and Darrin a $25,000 yearly retainer plus $1,000 per month for the privilege.

Even the Hibbard and Darrin molding–which always ran straight down the sides of the hood and then curved across at the bottom of the windshield–was retained in the GM cars. Only two years after concluding those first arrangements with Minerva, Hibbard and Darrin were known as the foremost designers in Europe. They were receiving twice the number of orders that they could handle and eager customers had to wait a year or longer before they could expect delivery.

The firm opened showrooms just off the Champs Elysees and finally boosted its production until it turned out magnificent, incredibly expensive limousines at the rate of 150 per year. When Hibbard and Darrin dissolved their partnership in 1928, Darrin had developed his abilities and reputation to such a point that it did not break his stride.

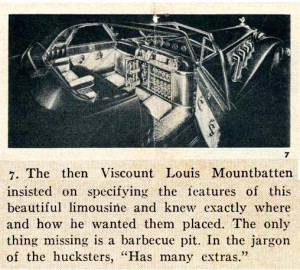

He formed a new partnership with a French banker and named the firm Fernandez and Darrin. He was retained as a consulting engineer by most of the great European manufacturers as well as Stutz, General Motors, Dodge, and Studebaker. When he designed for the Barker Coachworks of London, they put his nameplate beside their own ancient crest–an honor near equivalent to an introduction at court.

Darrin had become a name with magic in it. His cars stopped crowds all over the world. And bold, new ideas still poured off his drawing boards–such as the drophead coupe which he developed and introduced. In his search for a way to lengthen the hoods of his more “sporty” models, he invented under-the-cowl steering (see page 34, top left photo).

Darrin had become a name with magic in it. His cars stopped crowds all over the world. And bold, new ideas still poured off his drawing boards–such as the drophead coupe which he developed and introduced. In his search for a way to lengthen the hoods of his more “sporty” models, he invented under-the-cowl steering (see page 34, top left photo).

Besides increasing the racy appearance of his sports models, the design improved overall visibility to such an extent that Darrin was awarded the Brevet D’Invention.

By the early Thirties Darrin had passed the experimental stage in the development of his art, and had become confident, controlled, and even subdued in his techniques of design. As he puts it, “When we first started in Paris, nobody knew anything about designing cars.

We used to clutter them up with molding and ornaments because we didn’t know any better. But I tried to avoid ornamentation as I learned more, and to build the car so that its lines alone were enough.”

The latest cars he designed in Europe show amazing flexibility in concept. Some of his cars achieve their effect through a feeling of massive power (see the Panhard photo on page 34, lower left) while others attain beauty through graceful, flowing curves (see center lower photo, page 34).

At the peak of his successes in Europe the devaluation of the dollar and the ominous international situation in 1937 caused Darrin to pack up and return to America. His arrival in California has already been described. After an overwhelming success in selling all of Europe on the idea of an American coachbuilder, it was not too difficult to sell Americans a world famous Parisian designer.

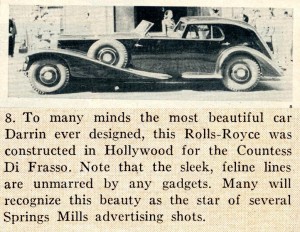

Once Darrin settled down in Hollywood, he completely discontinued the use of molding and designed his cars with clear, sweeping lines that were almost totally unencumbered with ornaments. One of his most beautiful cars, the Rolls-Royce designed for the Countess DiFrasso, is absolutely devoid of anything that might be called decoration. More than any other single car, it demonstrates that Darrin had reached that point of artistic maturity where he could forget tricky technique and think in terms of pure form.

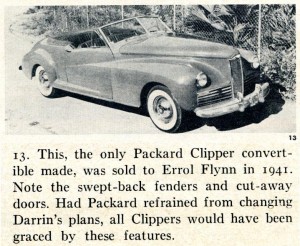

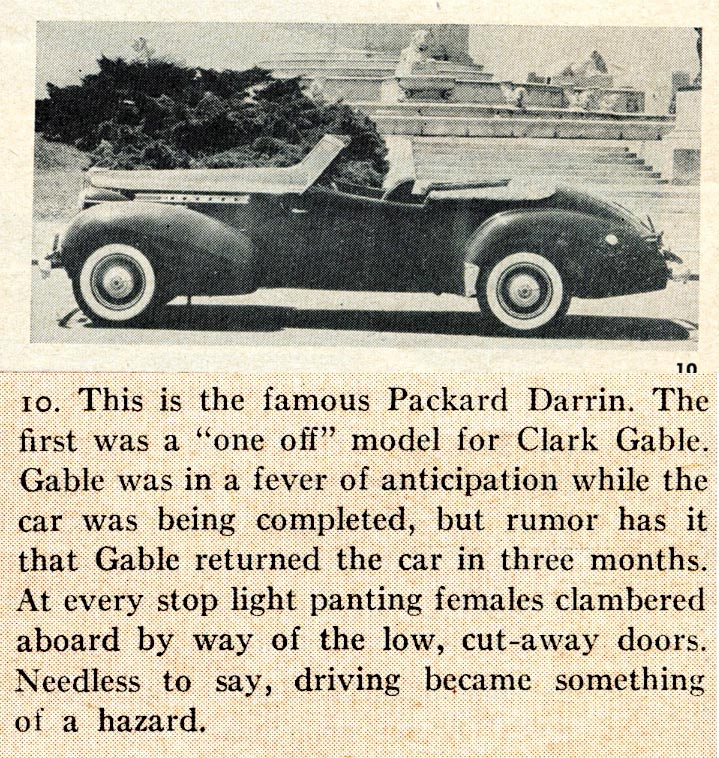

Strangely enough, this car was one of the last “one off” cars that Darrin constructed. The shop on the Sunset Strip had started well. Rudy Stoessel and Burt Chalmers (who are now partners in Coachcraft Ltd. of Hollywood) were in charge of construction and sales and the shop was well organized. Darrin was turning out incomparable cars; but from the standpoint of the classic car fan, things went to pot when the first Packard Darrin was delivered to Clark Gable.

The car was too good, and so many orders were received that Darrin had no time to think of anything else. About 15 were constructed on the Sunset Strip, and then Packard took over production. From that time until the war started, Darrin was immersed in the details of designing production cars for Packard.

The war stopped everything, of course, and Darrin went out of business as a designer. Since he had served as an air observer with the 71st Escadrille during the first world war, and had spent some time in 1919 as a manager of a scheduled airline, Darrin was chosen for the post of field commander in an army contract flight school.

Actually, it was a good job, but Darrin was never satisfied with it. He had wanted to fly himself, but both the Canadian and United States air force had rejected him for being beyond the age limit.

Almost immediately after the war, Darrin was placed under contract by Kaiser and stepped into a bitter feud with the salaried designers on the plant payroll. Although he was doing handsomely from a financial standpoint (he received 75 cents for each Frazer, and 50 cents for each Kaiser that came off the assembly line) his ideas were either ignored or distorted beyond recognition.

However, through the benevolent intervention of Kaiser himself, he saw his ideas brought to fruition in the 1951 model. It was put into production with Darrin’s plans almost unchanged, and before the paint was dry on the first model off the assembly line, the car won the Grand Prix D”Honneur at the Cannes auto show.

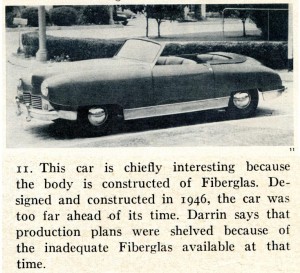

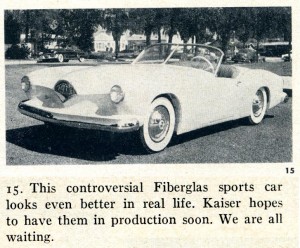

Although Darrin’s contract with Kaiser forbids him to do any free-lance designing, he is far from inactive. He is at present furiously engaged in the preparation of five new Fiberglas sports cars for delivery to the Kaiser factory. If everything goes well, these cars should be in factory production within a year and will be sold at around $2,800.

Like almost anything Darrin does, the new sports car is radically original. The top folds completely out of sight under the rear deck. Cleverly designed sliding doors remove the worry about curb height, so the car is extremely low–only 34 inches. It is constructed on a Henry J chassis, and with the light Fiberglas body to improve the power-weight ratio, the car may fill a long-felt need in this country.

Let us hope that Kaiser adds a respectable power plant and pays some careful attention to the suspension system. It is obvious that the King of the Coachbuilders is still willing to fight for his crown, even against such formidable antagonists as Ghia and Farina.

Darrin is a healthy, athletic-looking man who shows little sign of his 50 and some odd years, and he drives himself with a furious energy that wears even his younger assistants to the ground when they try to match it. It is an interesting situation, Nash has Pinan Farina, and Kaiser has Darrin. Both companies have demonstrated that they are willing to chance something new.

Darrin is a healthy, athletic-looking man who shows little sign of his 50 and some odd years, and he drives himself with a furious energy that wears even his younger assistants to the ground when they try to match it. It is an interesting situation, Nash has Pinan Farina, and Kaiser has Darrin. Both companies have demonstrated that they are willing to chance something new.

We can be sure that something will pop somewhere.

Summary:

I hope you “Kaiser Darrin” fans will appreciate the detail on Dutch – Motor Trend did a great job on the telling of his history back then, but much happened after 1953 and there’s still more to tell. Stay tuned at the same “fiberglass” time and the same “fiberglass” channel for more stories on Howard “Dutch” Darrin and his postwar sports car (and fiberglass) designs.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

Thanks for doing this extensive piece on Darrin, he was certainly one of the most innovative of designers, and a legend to this day. Rightfully cars with his bodies fetch big bucks and are still centerpieces in many large collections. Certainly a self promoter but one with extraordinary talent.