Well now I’ve gone and done it.

I’ve been searching for articles on automotive styling schools that appeared in magazines of the ‘40s and ‘50s, and recently I started looking in magazines of the ‘60s. I checked a rather rare book on customizing – it was a special edition in ’64 and not a magazine article. And in it….

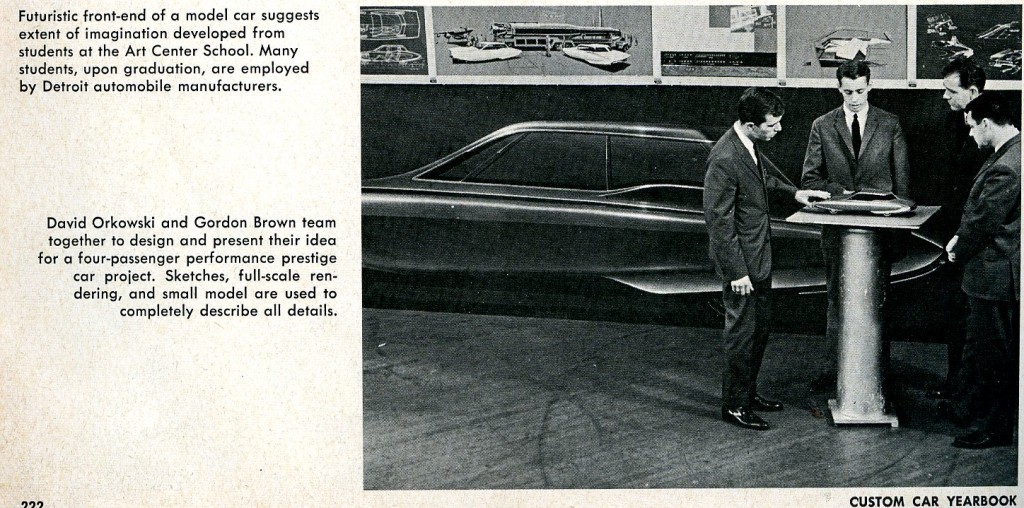

I found the best article on the Art Center School of Automotive Design that I’ve ever found – circa 1964.

I’ve shared articles about this famous school time and time again, for it was from this font of design imagination that many of the guys who designed and built fiberglass cars in the ‘50s and ‘60s either attended or were influenced by.

This is a very long and comprehensive article – breathtaking in its detail, so it’s with great pleasure that I share the content and the pictures with you here at Forgotten Fiberglass. It was written for the young man considering a career in design and discussed the Art Center and a local vocational school as well in terms of customizing and fabrication.

So….the following article is extensive – 5000+ words – get some coffee, something to eat and munch on and…

Off we go!

And remember….use your mouse to click on each picture and make it very large on your screen.

Have at it gang 🙂

Your Place In Customizing

Chapter 10: Custom Car Yearbook #2 (1964)

Petersen Publishing

What makes a good designer–of cars–or anything else? Where do they come from? What special kind of people are they? Or are they a special kind of people? Top business management would like to know the complete answer to these questions. It would save them a lot of time, and it would make them a lot of money.

Design talent can come, and does come, from almost anywhere. It does not tax believability to say for certain that a number of the readers of this book have such talent. This universality of the source of good design talent makes it an intriguing potential and a devious problem at the same time. It is to be found everywhere–but it is difficult to extract.

But it is true gold to business of all kinds–especially the automobile business–so it is worth a lot of tedious extracting because the real thing pays tremendous dividends.

There are three principal ingredients in the successful designer today. One is a fertile imagination from which ideas in good taste can flow; the second is a driving determination to express those ideas; and the third is a basic, facile talent and ability to translate those ideas with the mind and with the hands. There are few limits to the opportunities for young designers with these qualities.

We will discuss here primarily the qualifications and the available education for those young men who are interested in the design of transportation vehicles. However, we will also generalize in some degree on the whole subject of design since experience has shown that those who begin with the basic intention of becoming automobile designers often find interest stronger in closely related fields.

Although the word is somewhat misleading, the fundamental in all design is Art–not just the fine art that most of us associate with the word, but the art which is an integral part of our lives, in everything we live with, natural or manufactured. It is embodied in the whole world of communications, in the illustrations and photographs for our advertising, and in the books and publications which influence us.

It is also in the form and line and color of our instruments of living, our telephones, our washing machines, and our automobiles. The three principal ingredients we referred to above must be properly combined and carefully refined through some form of education.

For it is almost a certainty that the young designer will need formal training. And the extent of his success will depend to a large degree on the quality of his general and specialized instruction.

There are hundreds of art schools through the country, many of them with excellent reputations. But in the field of automotive design education, one school stands out–the Art Center School of Los Angeles. We will base our observations on the philosophy and program of this school since it epitomizes the best that is offered to those interested in this field and to those readers of this book who believe they might like to promote their interest in automobiles to a professional level.

At Art Center it is believed that there is a certain sensitivity in all of us and that there is talent in many of us for real creative expression. It is believed that there is no substitute for this talent, and that it is very much like good taste and imagination. Not all, by any means, have this talent–but it is apparent wherever it appears and it may appear almost anywhere.

The school feels that its job is to develop and guide this talent into the channels where it can perform best. At Art Center no sharp line is drawn between fine and applied arts because there is a mutual benefit which derives from their interdependence, especially in the early years of training.

The school feels that its job is to develop and guide this talent into the channels where it can perform best. At Art Center no sharp line is drawn between fine and applied arts because there is a mutual benefit which derives from their interdependence, especially in the early years of training.

The principal job is to apply good design to the functional in the creation of the new and the improvement of the old. Art Center is a school where students are made professional by professionals. Every member of the faculty is active in his own field of instruction. He spends part of each week at school and the remainder in his own studio.

This proximity to the demands of contemporary business and industry gives full opportunity for individual expression but prevents any possible escape into pure theory. The methods and procedures in the school’s classrooms parallel the professional experience of the staff and the industries they serve.

Along with the student’s development in creative expression at Art Center goes his general education–his understanding of the problems, the ethics and the esthetics of life. The school was founded in 1930 by a small group of professional artists headed by E. A. Adams, the present director.

It is accredited by the Western College Association as an institution of higher learning and is a member of the National Association of Schools of Design. Facilities include an auditorium, studios, classrooms, photography, stages, laboratories, projection rooms, conference rooms, library, gallery for student exhibits, offices and cafeteria.

The school offers the Bachelor of Professional Arts degree in five major courses–Industrial Design, Advertising Design, Illustration, Photography, and Painting.

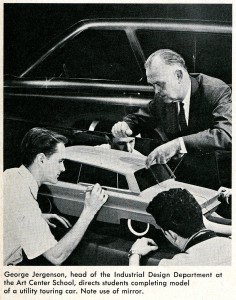

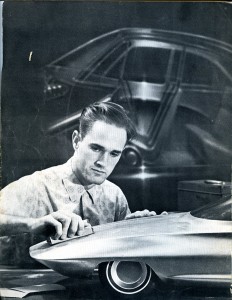

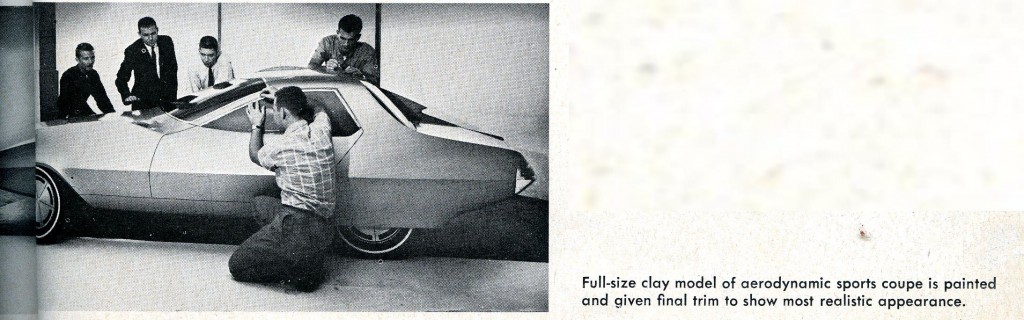

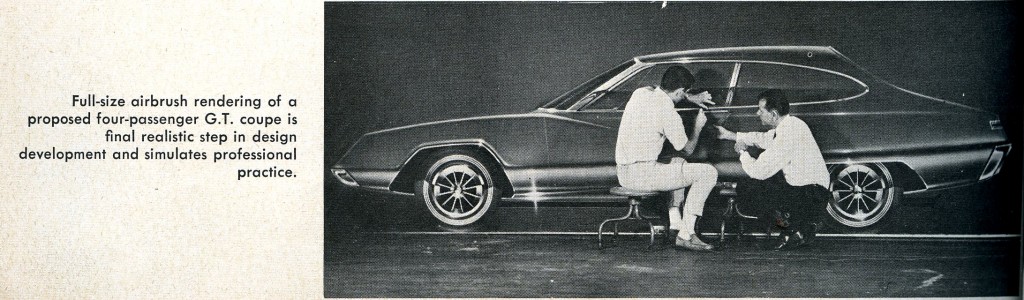

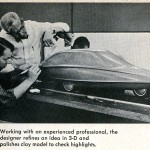

The Industrial Design Laboratories are completely equipped for the building of prototype models. The model shops have electrically controlled clay ovens, fiberglass facilities, separate areas for plaster casting, professional spray booth processing and all the necessary power equipment.

The photographic laboratories–and photography is a vital element in the treatment of industrial design–are designed for professional production. The black and white laboratories are furnished with enlargers, washing, drying, and mounting equipment and individual negative development rooms. The color laboratory includes the latest equipment for Ektacolor and other contemporary color processes.

The scenic and climatic advantages of Southern California have aided further the Art Center School’s ability to project good design education. Location sites used by the motion picture industry are selected for regularly scheduled field trips of both design and photography classes which often work together in special projects.

These groups visit such places as the Ghost Towns, the old Spanish Missions, the snow-capped mountain areas of the California Sierra, Death Valley and the deserted Bad Lands, for special illustrative and photographic coverage of products designed at the school or selected for special study.

Art Center believes that the instructors are the most important single force in any school, that the best criterion of competence is an instructor’s genuine professional achievement. Continuous significant professional activity is a requisite for teaching at Art Center.

The members of the faculty are designers and artists who divide their time between their professional practice and their classes. They bring to students a wide range of experience which makes their teaching stimulating, immediate and compelling. They are in a sense living textbooks. They teach mainly because they have an interest in young talent and the ability to communicate their experienced knowledge.

The worth of a school is measured by the achievement of its graduates. Art Center has for years received many more requests for its graduates than it has been able to fill. Personnel representatives from major corporations, agencies, and design offices come to the school regularly to interview and employ designers even before they graduate.

Others are placed through arrangements made by the school with the employing company. Art Center considers proper placement a major responsibility to the graduates and the employers. The school’s primary purpose calls for specialized professional training and sound general education.

A student begins to become a professional the day he enters Art Center. Every instructor treats him as a future professional. Every project he undertakes is designed to educate his mind, challenge his creativity, and equip him with the necessary skills.

By developing his talent and capacity he leaves Art Center as a competent designer ready for productive, creative work and conditioned for growth. Within the Industrial Design Department students may major in Transportation Design, Product Design, Packaging, or Design for Merchandising.

This, in a brief sense, is the background against which Art Center operates. But before delving further into details of the training for designers at Art Center, it might be well to explore the self-searching requirements on the part of the young aspirant, perhaps the very reader of these pages.

There are some very fine lines to be drawn between those young people who follow such avocations as custom car design as a temporary hobby as opposed to those who have found, in custom car design and related activities, a means of expressing a driving, ambitious desire to design things better than they are.

Sometimes there is a strong combination of or link between the hobbyist, the adventurer in custom car design and the young man who has a sincere desire to become, as a life profession, the designer of transportation vehicles or other products.

Sometimes there is a strong combination of or link between the hobbyist, the adventurer in custom car design and the young man who has a sincere desire to become, as a life profession, the designer of transportation vehicles or other products.

The school has found in its many years of experience that the young man who becomes a successful professional designer is one who has drawn his own ideas of how cars, trucks, planes, products, structures should look from the time he was extremely young–that the healthy dissatisfaction with things as they are springs early in the potential designer’s breast.

These basic desires to express one’s own interpretation of one’s own imagination and taste are basic in the best designers. They are sharply defined from those young people who would rather copy something done by someone else, or reproducing from what is available.

It is vitally important that the two types of individuals be separated, if possible before the expense of specialized education is involved.

And yet it is also important that one not lose a creative ability by assuming that the hobby is only a hobby. Prior to any determination on the part of a young person to enter the field of design education, a great deal of self-searching and counseling would be advisable. Once it has been determined that the desire to learn to draw and design and the drive to express individual opinions in these fields the young person should make his own decision.

Most good designers can’t avoid being designers. They are driven to it as to any habit. Once that habit is established, the rest of the requirements can fall rather easily into place. Given the genuine drive and desire and intelligent imagination from which to call forth tasteful ideas and the ability to express those ideas fluidly the education can become rather facile and enjoyable.

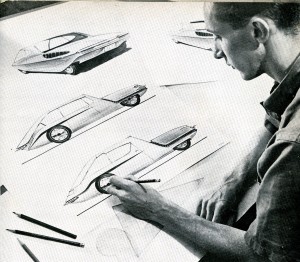

The education of the professional artist is based on a broad foundation of concept, knowledge, and skill. Before the future designer can begin to study professional approaches and the techniques they require he must develop an understanding of the drawing language.

Drawing is to the artist and designer what mathematics is to the engineer, his means of communicating his ideas. Only after he has acquired a working knowledge of this language can he begin to do real creative work.

Basic art studies are taken by all students at Art Center no matter what the major course is to be. They include such important studies as life drawing, head drawing, illustration, analysis of form, perspective, design structure, and analytical drawing.

In these courses the student learns and applies the basic principles of design and orientation, the laws of free hand and projection perspective. He sharpens his eye and also his perception. He learns to draw not only what he sees but what he knows. He achieves freedom in expressing ideas and emotions through symbols.

He develops a vocabulary in the language of line, form and color. He begins to learn how when and why to use the many elements of this language.

The basic art studies not only lay the foundation for later specialized work but they also make possible important exploration into many new areas and often reveal a student’s special talent. While many students have chosen a professional objective before they enter, stronger potential for another field sometimes is discovered early and enables the student to change his major advantageously.

At the same time he is taking the basic art studies, the students are taking Lower Division courses in one of the school’s five professional departments like Industrial Design, and in the Division of General Education.

It is probably true that the automobile has done more to change man’s living habits than anything else in the past 100 years. The automobile industry is one of the mightiest elements in our economy. Art Center School recognized 30 years ago the need for sound training in the design of transportation vehicles, mainly centered around the automobile and its relative products.

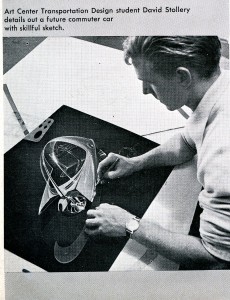

This specialized field offers a chance for a fine contribution from the young, enthusiastic designer. At Art Center School, along with his other studies, the student majoring in transportation design begins with the study of drawing. It is almost impossible for him to express himself otherwise.

He must learn to talk on paper and with all kinds of media. He must learn the basics in color, perspective, surface development, line and form.

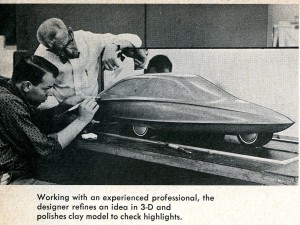

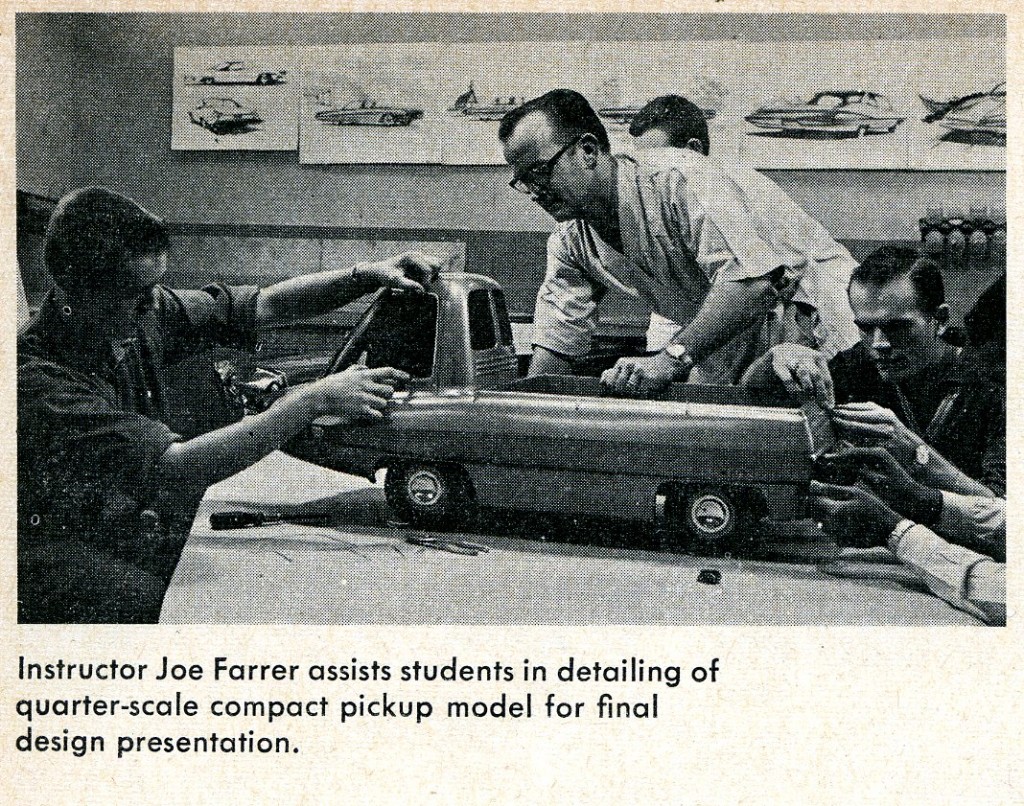

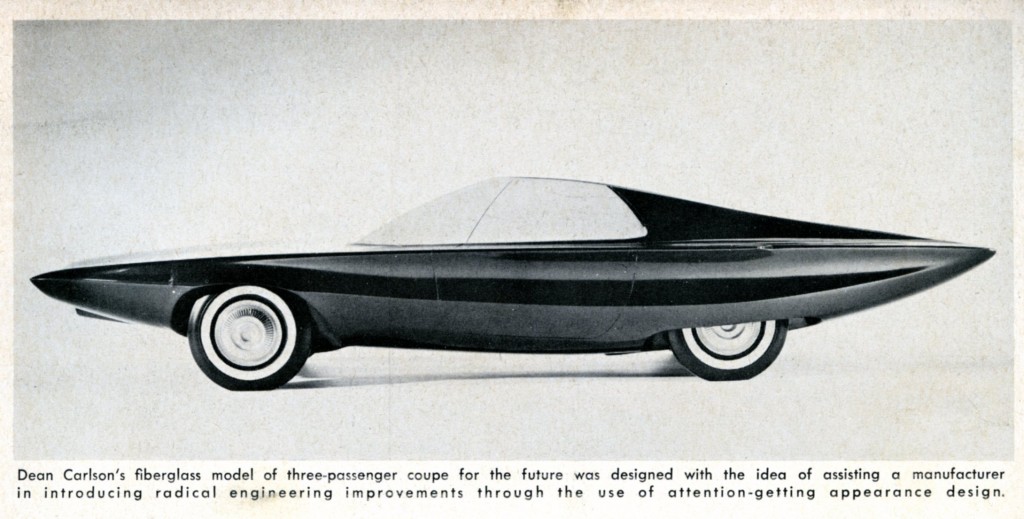

The study of model construction also is important in this student’s curriculum. He is encouraged and trained to construct, in clay, plaster and plastics, original and workable ideas with just one aim in mind–to improve what exists.

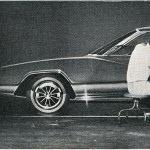

The young designer at Art Center also learns the ways and means of self-expression in other forms, in written reports or oral presentation and participation in conferences. He is encouraged to reach out in his exploration of new designs for cars, boats, trucks, trains, planes, and helicopters–and now, space vehicles. But he is soundly anchored to common sense in his general education at school.

Usually upon graduation a transportation designer joins the staff of a large car manufacturer where he may progress through various studio work. He may one day head a studio or work as an adjunct to top management in styling for the company. Others join independent styling organizations, go into related fields, or set up their own studios.

Almost half of all of the automotive designers in the studios of the great Detroit companies are ex-Art Center students. A number now hold executive positions in Europe and America. In the pursuit of studies in transportation, the school is favored by the full cooperation of Detroit’s large companies as well as the world’s outstanding independent designers.

Almost half of all of the automotive designers in the studios of the great Detroit companies are ex-Art Center students. A number now hold executive positions in Europe and America. In the pursuit of studies in transportation, the school is favored by the full cooperation of Detroit’s large companies as well as the world’s outstanding independent designers.

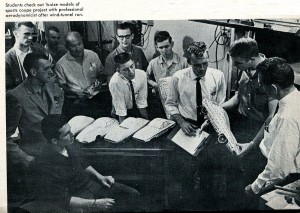

The latest model cars are furnished by these companies so that Art Center faculty and students may do extensive study and testing. Some of the companies issue special assignments to the advanced student classes at the school and regularly evaluate the progress made on these assignments throughout the terms in which they are being completed.

Another major course in the Industrial Design Department is Product Design–which is just what the term implies–designing almost everything that is produced. The field is practically limitless. It includes all of the things we live with every day, the necessary, the convenient, the luxurious, the pleasing, and the practical.

The product designer must begin with a wide and insatiable interest in what makes things function, how to make them look and function better. The best product designers are facile artists with especially inquiring minds. In the designing of household appliances or any of the everyday tools of life there must be sound art principles of form and line and substance.

But the product must operate properly and perform the job. The designer must have enough engineering know-how to understand the essential mechanics. He must know that they will fit and function within the confines of his design.

A third outlet for Industrial Design majors is in the field of Packaging. The need for packaging has existed since primitive man took his goods to the market place in baskets and pots. There has always been the container and the identifying label. Modern sanitary packaging has eliminated the cracker barrel and today food comes to the consumer in foil, plastic, glass, paper, and metal. From the smallest pill to the king size mattress products reach the market safely and attractively in packages and with the informative as well as the sales-promoting label.

Modern self-service requires that packages sell themselves. Television commercials demand that packages identify themselves quickly. Trademarks, symbols, and colors create family package identification, leading to the public easy recognition and acceptance. Design of the package must sell both the product and the manufacturer to the consumer. The well designed package can convey the stability and character of the manufacturer and the product.

The good package designer of today must understand psychology and people’s reaction to color and symbols. He must be able to interpret the findings of market researchers and analysts. He must cooperate with advertising and merchandising experts and frequently design supporting display materials.

Another special course in the Industrial Design Department at Art Center is called Design for Merchandising. Putting the customer in an atmosphere conducive to product acceptance is the function of the merchandising designer. The “customers” may be anyone–the board of directors in the executive offices of a large corporation, housewives in the community shopping center, or visitors to a special exhibition at a world’s fair.

In any situation the designer’s job is to place the customers in a surrounding of believability which is pleasant, to make the goods, whatever they are, attractive and desirable. These, then, are the specific subjects in the Industrial Design department of what is probably the nation’s leading school of design. Some of the description ranges far afield from custom car work and the type of hobby which many readers of this book enjoy.

But, as has been said, the school has found that there is no boundary for talent, that basic talent may change its course easily and find its way into varying fields of productive creativity. It is not a wild stretch of imagination–rather it is almost a certain possibility–that a number of the readers of this book will eventually find their way into industrial design fields described here.

The very interest many of you have in customizing cars indicates the kind of latent talent which will lead to high quality performance in industrial design fields. Those who will stick intuitively and naturally to the design of transportation vehicles should allow nothing to stand in the way of that strong desire to change things from what they are to something more attractive, more functional, and more acceptable.

The principal recommendation to teenagers and young adults whose interest in custom cars has led them to this article is that they should enjoy these explorative ventures, have fun, and avoid serious consideration of careers until they are certain they have a drive toward designing–designing anything.

Then the time is ample for refinement and for selection of courses of study leading to a satisfying profession, through which they can earn good incomes, as well as make outstanding contributions to the shape of the future.

After acquiring the education and knowledge offered by such institutions as the Los Angeles Art Center School, the student desiring practical application courses should look into the trade technical schools. Nearly every major city has such schools where the person who has a natural ability in the use of his hands can develop these skills.

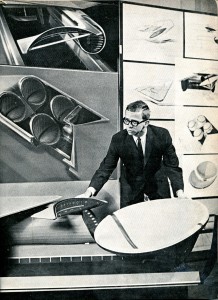

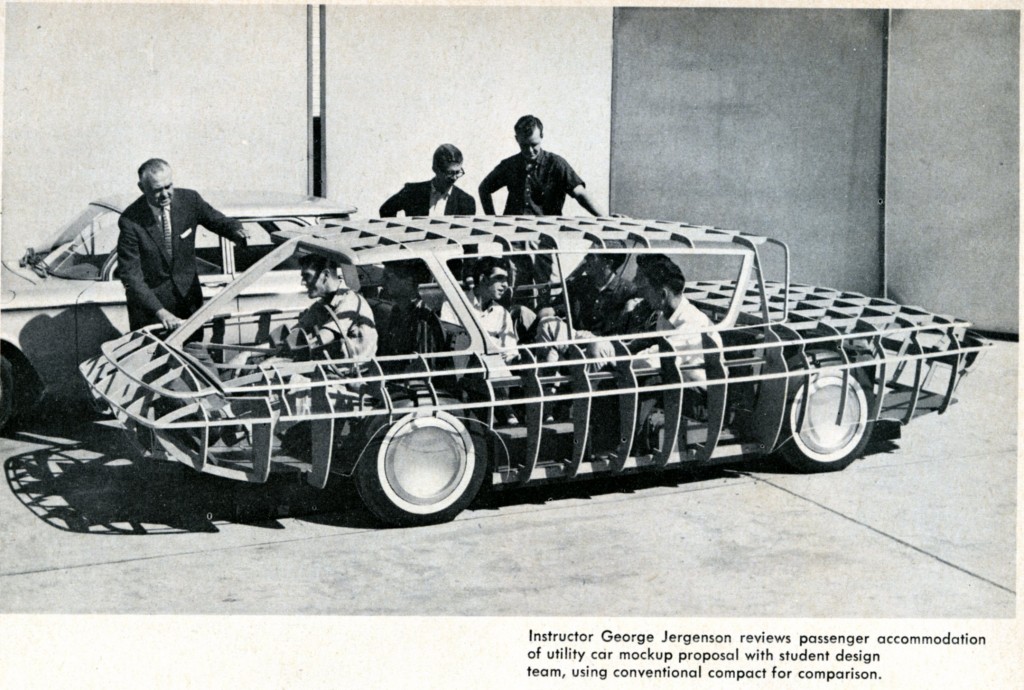

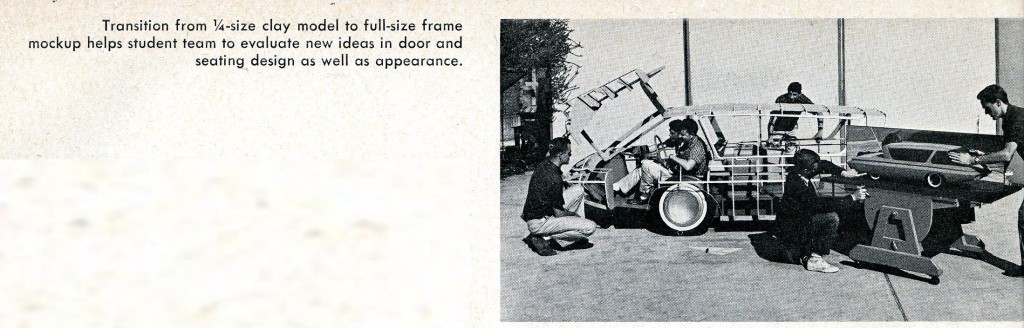

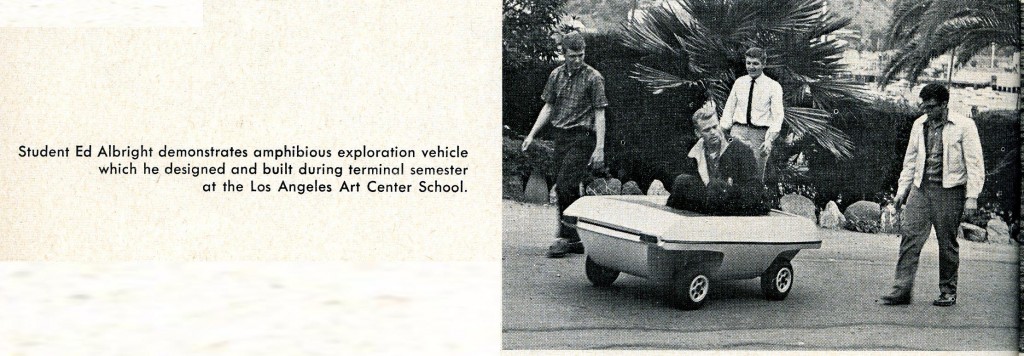

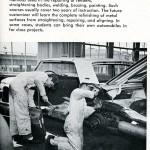

Such training in the manual arts is so desirable if he is considering even the smallest type of restyling project on his own car. On these pages, you’ll see students depicted in practical application courses that are currently being offered by one such school, the Los Angeles Trade-Technical College.

Here, the restyling enthusiast can develop the skills, basic knowledge, and methods used in the repairing of fenders, straightening bodies, welding, brazing, painting. Such courses usually take two years to complete, but once through, the student should have a thorough knowledge of all of the basic body repairing methods which he can apply on his own restyling project.

You may have read elsewhere in this book about some of the top customizers–the Alexander brothers of Detroit and George Barris of North Hollywood–who started right into customizing automobiles without any previous basic training or experience.

This may be so, but they will be the first to tell you that this is the hard way to do it. So, we say here and now you can profit by their years of heartbreaking experiences. Yes, many of the early cars on which they worked never really “got off the ground,” so to speak. George Barris can attest to the “junkers” he created in the early days of his Lynwood, California, shop.

These may not have been many, but the point is even one such unfinished customizing project represented hours of toil, sweat, and tears which probably could have been avoided had he been blessed with basic training in his early days of customizing. Of course, through the years, George sought out knowledgeable people and did take special courses of instruction which elevated him to his role today as “King of the Kustomizers,” as one magazine once headlined an article about him.

Let’s further consider what you’ll learn at a trade technical school. One of the first problems the serious custom car enthusiast will encounter is that of learning the proper technique of welding metal. Once he’s mastered the torch, there’s no limit to the type of metalwork that he might tackle.

At such a school, you’ll learn that the Linde Air Products “Prest-O-Lite” #420 unit is typical of the torch equipment available throughout the United States today. Such equipment will cost you from $75 on up. It will include blow-pipe and tips, oxygen and acetylene regulators, hoses, friction lighter, goggles, and combination spanner wrench for the various fittings.

You also learn that you’ll need a pair of pressurized cylinders of oxygen, and acetylene. These will cost about $50 for the pair, but then you may get the re-fills for about $4 each.

With this torch you’ll learn that you can do both welding and cutting with the same tool, merely by changing the nozzles and certain valve controls. Mastering the hang of torch welding, you’ll find, will take considerable practice. For instance, proper penetration depends more upon heat control than any other factor. Should the metal be too cool, penetration will be poor. Too much heat, on the other hand, will cause “burning through.”

You’ll learn brazing. This is the method of bonding metal together by using a lower torch heat; you don’t actually melt the two pieces of metal to be joined. You merely get them hot and the bonding is accomplished by the brazing flux and the third metal, the brazing rod.

In brazing, you use a smaller tip on the torch to keep the torch heat down where you want it You’ll also learn that brazing requires that the metal to be worked on must be absolutely clean–not just clean in appearance, but chemically so. Unless this is done first, the brazing rod will not stick to the surface, but instead merely run off. Proper handling of the rod, flux and control of relative temperatures is the knack of brazing–one that you can soon master with a little practice, which you’ll get at any trade technical school.

Another process that you’ll learn is the art of torch cutting of metal. Metals of 1/8-inch or greater are usually cut with a torch. All you have to do is change to a cutting tip on the torch; the tool has a button beneath the handle which administers straight oxygen on demand. Some tools, it should be noted, a separate cutting attachment is used; it consists of a different blow pipe which incorporates an additional oxygen passage.

Straight oxygen is administered by a regulator lever, or control, when required. In performing the cut, you play the flame along the path you want the cut to follow. This is the pre-heating procedure. When the area to be cut glows bright red, the metal has reached its kindling temperature. You then press the oxygen control that administers the oxygen “needle.” This does the cutting job, unless you’ve misjudged the temperature of the metal and it isn’t hot enough yet. A clean cut indicates your pre-heat technique was correct, but if the cut is sloppy or if beads have raised along the edges, you’ve got too much pre-heat. Practice will see you through, so don’t despair should you not get a clean cut right off the bat.

Besides welding, you’ll learn the technique of working metal. You may have the great restyling ideas in the world, but if you’re a gross amateur when it comes to shaping, forming, contouring, bending metal–you had better turn your job over to a professional body shop or learn your trade before tackling a major project.

For instance, one of the most common mistakes the beginner makes is that of warping body panels. Warpage can happen in several different ways–too much heat, too much pounding, perhaps. The stretched metal may have a distinct bulge in it. This must be corrected if you ever expect to receive trophies for your body restyling. First, you find the pressure point in the bulge and relieve it by shrinking the metal.

You can do this by pounding the bulge in and out with hammer and dolly after you’ve heated the center point of the bulge with a small pointed blue flame torch. With a dolly behind the metal panel where it has been heated, start slapping the heated spot with a curved rough file slapper, or spade, until the area becomes smoother. Then, taking a cold wet wire rag, apply it immediately to the hot area.

This will contract the metal and take the bulge out of the stretched out panel area. Sounds complicated. It really isn’t too difficult, but you can learn how to do it faster by practical application courses offered to you at the trade technical schools.

What about the tools that you’ll be needing for your restyling project? You can’t get along very long without a body grinder and an electric drill. Don’t confuse a body grinder with a buffer. Buffers operate at 1500 to 2000 rpm, while body grinders turn from 5000 to 7500 rpm. Some body grinders have two speeds. A body grinder, you’ll learn, is equipped with a bakelite backing plate used for support of the actual cutting disc, which consists of a flexible rock-glued adhesive material available in either seven or nine inch diameter sizes.

The body grinder, which you can purchase for about $85 on up, is used to remove paint, remove low spots on the metal, and to generally work smooth the metal surfaces of a given area, whether it has been welded, leaded, hammer and dolly straightened and contoured. The discs available for the various operations are designated with identifying numbers running from 80 (fine) down to 16 (coarse) with the smaller number the larger the grit. For removing paint and ordinary body work, a 24 closed coat disc is used; for finish smoothing, a 50 closed coat disc is common.

The home customizer will also have to learn how to lead. The correct leading technique is most important in avoiding warpage, high spots, low spots, and generally uneven surfaces. At a trade technical school, the restyling enthusiast will learn the correct preparation of the metal for leading, proper use of the torch to obtain good adhesion, bonding, and forming of the metal. The best lead to use is designated as 70/30 which, broken down, simply means that this lead consists of 70 percent tin, 30 percent lead. The reason for such a high percentage of tin to be desirable in the lead is that tin will hold heat, allowing the alloy more time to form; it’s also creamier and smoother to work.

The Future for Customizing

Despite re-vitalized efforts on the part of Detroit automobile manufacturers to provide the motoring public with vehicles which are more pleasing to the eye than ever before, we see no let-up in the hobby of restyling production cars. The sport has mushroomed out from the west coast across the nation, with the east and middle west now having more active enthusiasts than ever before. Today there are more than 700 inividual custom car shows each year, held in small villages up to the largest cities in the country. The cars exhibited in these shows are all the way from very mild customs up to complete handbuilt vehicles from the ground up. Many of the latter are excellent examples of the cars of the future, each a vivid illustration of imaginative genius of design and detail, a tribute to the youth of America who are willing to put their individual talents to work.

Customizing, or the art of restyling automobiles, is certainly not a static hobby. Every year there seems to be more and more recruits who actively engage in the craft. The only prediction worth a hoot concerning the future of customizing is the fact that it’s bound to be with us for years to come.

Summary:

I hope you enjoyed this window into an exciting time of styling and design in America – and the the history of the Art Center of Los Angeles / Pasadena too.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

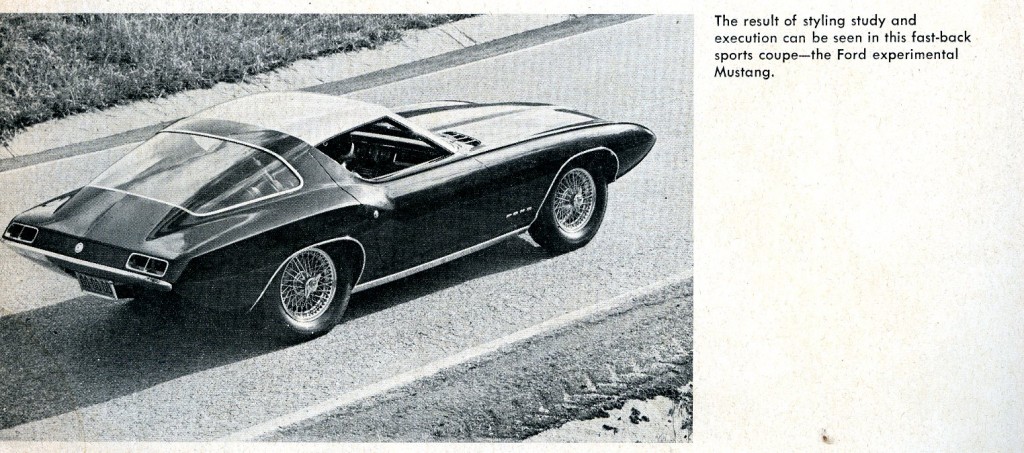

I clearly remember seeing the ‘first’ pictures of that futuristic Mustang model, but it was initially a covertable as I recall…the fastback was shown later.

Many thanks Geoff for posting this article.

This is a superior article that puts in perspective all of the talents (amateur or professional) and techniques required to create superior designs, automotive or other.

I’m sure that there are within the ranks of the Forgotten Fiberglass followers many designers (amateur or professional). There must be many great stories and adventures that will add to the lore of the great fiberglass creations of years past. Not just fiberglass cars but automotive and industrial design in general.

How about it gang? Send your personal design experience stories (amateur or professional, industrial or automotive, small or large) to Geoff.

I have a story that I’ve wanted to tell since 1960.

Happy Glassin’

Bob Peterson

Though this came out in 1964, most of the photos are ACS file pics from 1958 to 1961. The Corvair must be Mac’s in 1959. He painted it silver over black in 1960 as a study to give it more class. The full size coupe with Mac and 4 students was a design project to do a package about like the 1980s small Cadillac eldos. I still have some of my drawings. The idea of bringing back the classic look would eventually come with cars like the Mk III Continental in 1969.

The amphibious vehicle Ed Albright designed was shown at a Catalina IDI convention in the fall of 1961. I worked on it. It was an upper and lower fiberglass half with Dow foam in it long before it came in rattle cans. It was powered with a chain saw motor. That is me at the far right out on the island. We burned some mid-night oil the last couple of weeks to get it ready. The wheels were donated by an aircraft manufacturer.

The Art Center and Southern Cal had a student design contest. Most of students would become product designeers.